A Queen's Endorsement Launches Snuff Into European High Society

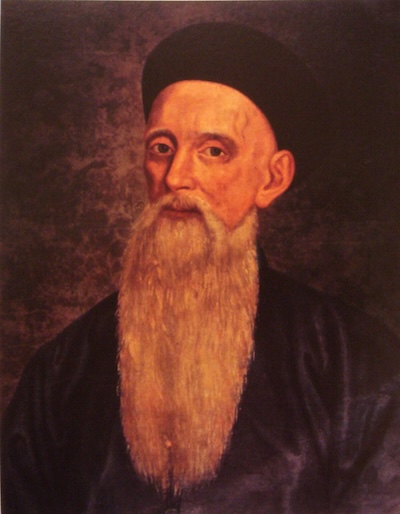

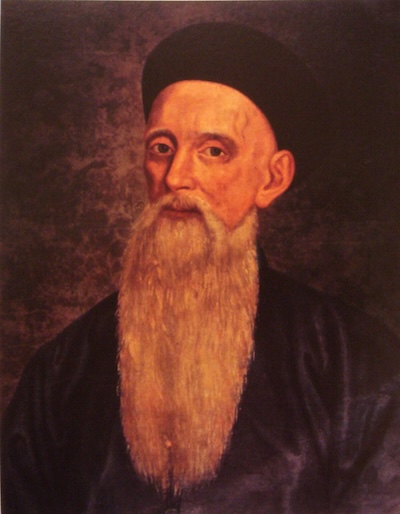

Catherine de' Medici, Queen of France, is introduced to snuff by French diplomat Jean Nicot and becomes a devoted convert. She finds it so effective for her chronic headaches that she declares tobacco shall be called Herba Regina (the Queen's Herb). Her royal endorsement helps popularize snuff among the French nobility and sets the stage for its spread across Europe. Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus would later latinize Nicot's name when naming the tobacco plant Nicotiana tabacum, giving us the word "nicotine."

Catherine de' Medici

Tobacco Travels East

Spanish explorers introduce tobacco to the Philippines, from where it spreads to Japan, Korea, and eventually China. Snuff begins appearing in Chinese port cities as a regular import from the New World and Europe, carried by the same trade routes that were reshaping global commerce. The primary gateway was Canton (Guangzhou) the great trading port on the Pearl River where European merchants from Portugal, Spain, Holland, England, and France maintained their factories and warehouses, and where goods, habits, and ideas from the West first made contact with China.

William Daniell's View of the Canton Factories (1805–1806)

(Image: Wikipedia)

The Snuff Bottle Is Born

Snuff becomes a luxury commodity across Europe and begins taking hold in China in the first half of the century. At first, the preference among Chinese users leaned heavily toward smoked tobacco rather than snuff, a habit that would persist among the lower classes throughout the dynasty. It is during this period that the snuff bottle emerges as a uniquely Asian solution to a practical problem. The European snuffbox proved disastrously ill-suited to Asia’s humid climate. Its large-hinged top allowed moisture to seep in and spoil the dry snuff inside, while its size and sharp corners made it cumbersome and awkward to carry.

European snuff box

(Image: Amsterdam Pipe Museum)

The snuff bottle solved all of this at once: small, soft-edged, and fitted with a tiny mouth that could be tightly stoppered against moisture and air. The bottle’s design evolved naturally from an existing Chinese tradition of storing perishables in sealed or stoppered vessels. Snuff imported from abroad was itself initially delivered to China in stoppered glass jars, and small bottles of sizes and forms comparable to snuff bottles had existed in China long before snuff arrived—examples have been found in tombs predating the introduction of snuff entirely. Chinese medicine bottles are also believed to have served as design inspiration. It is also possible that European traders themselves, recognizing the failings of their own boxes, introduced an alternative vessel that Chinese craftsmen then further developed. Either way, the result was an unqualified success.

Chinese medicine bottles

The Pope Draws the Line at Sneezing

Pope Urban VIII, sculpted in marble by the great Baroque artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini, issues a formal ban on snuff use in church and threatens excommunication for any snuff takers, including priests. He reportedly believed the act of sneezing was uncomfortably close to sexual ecstasy.

Bust of Pope Urban VIII

(Image: Wikipedia)

Russia Takes a Hard Line

Russian Tsar Michael I prohibits the sale of tobacco entirely and institutes a memorable deterrent for snuff takers: the punishment of having one's nose sliced off.

Czar Michael I

(Image: Wikipedia)

The Kangxi Emperor Keeps the Snuff

On the first of his six great Tours of Inspection to the South—undertaken in part to ease the animosity of a population that had suffered greatly during the Qing conquest—the Kangxi Emperor is presented with an assortment of gifts, including snuff, by two Jesuit priests in Nanjing. The priests, incidentally, would have been subject to excommunication under Pope Urban VIII forty years earlier. The Emperor returns all the other gifts but keeps the snuff, issuing a decree that its acceptance“meets our approval.” The Emperor was already thirty years old at the time and appears to have had prior knowledge of snuff before this encounter. It is one of the earliest and most telling records of imperial enthusiasm for snuff taking in China.

Kangxi Emperor

(Image: Wikipedia)

The Imperial Glassworks Is Founded

A pivotal moment in the history of the snuff bottle: the Kangxi Emperor establishes an imperial glassworks at the palace, placing it under the direction of the Bavarian Jesuit Kilian Stumpf. The founding of this workshop marks the beginning of documented glass snuff bottle production at court. Stumpf and his associates introduce European glassmaking techniques, including the faceting of glass using a spinning metal disc with abrasives, that would become hallmarks of the imperial snuff bottle aesthetic. By 1703, the glassworks is producing snuff bottles in a wide range of colors including red, purple, yellow, white, black, and green. Stumpf would remain at the helm of the glassworks until 1720.

Small faceted imperial yellow Kangxi glass snuff bottle

(Image: The Marakovic Collection - Hugh Moss - e-yagi.com)

The Snuff Bottle Becomes a Status Symbol and a Work of Art

Snuff taking becomes firmly established at the Manchu imperial court, and with it begins the snuff bottle’s transformation from practical container into treasured artistic object. It was the Kangxi Emperor who actively promoted snuff taking as a replacement for smoking, writing in a set of moral principles later published by his son the Yongzheng Emperor that he was giving up smoking permanently, as he could not ask others to abandon a practice he himself was unwilling to forgo. Once the Emperor embraced the habit, powerful courtiers followed obsequiously, and snuff taking rapidly became embedded in court ritual as a marker of elite status and a currency of favor and influence. Common all-purpose containers were quickly recognized as a mismatch for so prestigious a substance, and the palace workshops were enlisted to produce vessels worthy of the habit. Craftsmen also converted earlier jade works into snuff bottles, while private workshops around the capital supplied the newly devoted northern elite. The snuff bottle as a distinct category likely emerged within the first two decades of the Kangxi era, its design shaped not only by aesthetics but by the practical demands of the snuff stored inside. The type, texture, and origin of the snuff influenced a bottle’s shape, material, opacity, and the precise size of its mouth. The habit remains centered in Beijing and the north.

Kangxi cloissone snuff bottle

(Image: The Marakovic Collection - Hugh Moss - e-yagi.com)

Snuff Bottles as Imperial Currency

Records from these years document the Kangxi Emperor conferring gifts of both snuff and snuff bottles on worthy recipients, cementing the bottle’s dual role as functional object and prestigious symbol of imperial favor. A detailed account from 1703 by the scholar Wang Shizhen specifically describes glass bottles produced in the imperial glassworks being used for snuff storage and lists the range of colors then in production—one of the earliest written records to confirm what we now recognize as the classic Chinese snuff bottle.

A set of jade pebble snuff bottles likely prepared as gifts for courtiers

(Image: National Palace Museum)

Brazil Wins the Snuff Wars

Father Kilian Stumpf—the same Bavarian Jesuit who had founded and directed the imperial glassworks since 1696—presents the Kangxi Emperor with 48 vessels of “tabaco de amostrinha,” a celebrated Brazilian snuff and the most highly regarded in theworld. The gift reflects a well-established hierarchy of snuff quality: domestic Chinese snuff was produced in the provinces of Shandong, Sichuan, Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, while imported snuff from Spain, France, and Scotland commanded higher prices and greater prestige. Brazilian snuff sat at the very top of this hierarchy, the most coveted of all.

Brazilian Amostrinha snuff

(Image: Yeung Tat Che)

Yongzheng Emperor's Reign (1722–1735)

A Reign of Quiet Productivity

The Kangxi Emperor’s successor leaves no records referencing snuff directly and appears to have had limited enthusiasm for cloisonné—only one cloisonné vessel with a Yongzheng reign mark is known to exist. He does, however, write about tobacco and decries the negative aspects of smoking. It was the Yongzheng Emperor who compiled and published his father’s moral principles, including the Kangxi Emperor’s declaration that he was giving up smoking permanently. Meanwhile, palace workshop records from this era document extensive production of snuff bottles in a remarkable range of materials: glass, cloisonné, porcelain, jade, coral, ivory, tortoiseshell, amber, and gourd among them, many of which had almost certainly been in production since the closing years of the Kangxi reign. The earliest known porcelain snuff bottle dates to this period.

Yongzheng porcelain snuff bottle

(Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Qianlong Emperor's Reign

(1735–1796)

The Golden Age of the Snuff Bottle

The Qianlong Emperor is one of history's most prolific patrons of the arts, and snuff bottles number prominently among the vast array of objects he commissions. It is under the Qianlong court that the snuff bottle reaches its fullest artistic expression—these small vessels now reflecting, in miniature, the extraordinary creative achievements of the Qing Dynasty at its height. The relationship between bottle and contents remains intimate: the quality and character of the snuff being stored continues to influence every aspect of a bottle's design, from its material and shape to the size of its mouth, with elite snuffers holding firm opinions on what vessel was appropriate for which snuff.

Variety of Qing Dynasty snuff bottles

(Image: Sotheby's)

East and West Compete in Luxury

In both Europe and China, the mid-eighteenth century marks the height of snuff culture among the elite. In England, Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, becomes one of history's most extravagant snuff enthusiasts. Known popularly as "Snuffy" Charlotte, she devotes an entire room at Windsor Castle to her snuff stock. Her son, George IV, carries the tradition even further, changing his snuff according to the time of day and maintaining a dedicated snuff storage room in each of his palaces. That the same years coincide with the height of the Qianlong Emperor's reign in China—himself one of history's greatest patrons of the snuff bottle—speaks to the remarkable parallel hold that snuff had taken on the courts of both East and West.

_with_her_Two_Eldest_Sons_-_Google_Art_Project-min.jpg)

Queen "Snuffy" Charlotte with snuff boxes

Painted by Johan Zoffany (1765)

Still a Northern Habit

French Jesuit priest Jean-Joseph Amiot observes that snuff taking in China remains firmly centered on Beijing and the imperial capital, suggesting the habit has not yet spread widely beyond the court and the northern elite—though that is about to change rapidly.

Jesuit priest Jean-Joseph Amiot

(Image: Wikipedia)

A Most Unusual Funeral Request

The last will and testament of British woman Mrs. Margaret Thompson from 1777 instructs that her body be covered with the best Scotch snuff and her pallbearers each carry a box of snuff for refreshment along the way. It is a vivid, if eccentric, testament to the grip snuff had taken on British social life.

News clip from The Herald Democrat 1904

A Backhanded Compliment from the First British Envoy

Lord Macartney, the first British envoy to China, writes that the Chinese "take snuff mostly Brazil, but in small quantities, not in that beastly profusion which is often practiced in England." This remark was widely read as a thinly veiled jab at Queen Charlotte herself. His account also confirms that Brazilian snuff remained the variety of choice among discerning Chinese snuff takers.

Lord Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney

(Image: Wikipedia)

Snuff Spreads Across the Empire

Within roughly twenty years of Father Amiot's 1774 observation, snuff taking expands rapidly across China. References to snuff and snuff bottles in the writings of traveling Westerners become numerous from the 1790s onward. Snuff bottles from this period reflect the broadening of the market, with production expanding well beyond the imperial glass and cloisonné pieces of the Kangxi and Qianlong courts into a much wider range of materials and regional styles — porcelain from the Jingdezhen kilns, hardstone carvings in jade, agate, and crystal, inside-painted glass bottles, and painted enamel pieces among them. Snuff bottles from this period reflect the broadening of the market—a glass vessel dating to this era survives in private collection, still containing its original warm dark brown indigenous Chinese snuff powder, a tangible remnant of the habit at its peak.

Glass vessel containing indigenous Chinese snuff

(Image: Robert Hall)

Snuff at the White House

Dolley Madison was one of the great proponents of snuff in American public life, and her enthusiasm for it was legendary among Washington insiders. She took snuff freely and openly, untroubled by those who regarded it as a vulgar indulgence, and her snuff box—a monogrammed silver case engraved with her initials "DPM" and made around 1800 by Georgetown silversmith Charles A. Burnett—was said to carry an almost magical social influence, disarming even the most hostile guests. It was entirely in character, then, that with British forces threatening Washington and the capital in a state of high anxiety, she nevertheless hosted a White House dinner at which she served snuff alongside ice cream. The gesture perfectly captures both the woman and her moment—a hostess of extraordinary composure presiding over a city on the edge, snuff box in hand.

Dolley Madison's silver snuff box still preserved today at Montpelier, the Madison family farm in Orange, Virginia

(Image: Encyclopedia Virginia)

From Imperial Treasure to Mass Market

By mid-century, snuff taking has become commonplace throughout China, and the snuff bottle undergoes a dramatic transformation in its social role. The scholar and merchant classes replace the imperial court as the most important consumers, and the private sector takes over from the palace workshops. Regional bottle-making operations spring up across the country to meet surging demand, and the great Jingdezhen kilns fire thousands upon thousands of bottles. What was once an intimate art form produced for emperors is now a mass-market commodity—though the finest examples from earlier in the dynasty remain objects of rare beauty.

The kilns of Jingdezhen still operate today

(Image: Chinaxiantour.com)

A Special Greeting

A photograph from this era captures two horsemen—likely Mongolian—pausing to compare and discuss the snuff bottles each holds in hand. The image is an eloquent illustration of how far the snuff bottle has traveled from its origins in the imperial workshops of Beijing: small enough to carry on horseback, easy to handle and share, and now thoroughly woven into daily life across the vast reaches of the empire.

Two horseman greet each other with snuff bottles

End of the Qing Dynasty (1912)

The End of an Era

The fall of the Qing Dynasty brings the great snuff era in China to a close. The last emperor, Puyi, ascended to the throne as a child of two in 1908 and was forced to abdicate just three years later, bringing three centuries of imperial rule to an end. With the court dissolved and its rituals abandoned, the culture of snuff taking that had flourished under imperial patronage since the Kangxi Emperor faded with it. But the artistic legacy of the snuff bottle endures. These small, exquisite objects—born of a practical need, shaped by the demands of their contents, elevated by imperial patronage into works of art, and ultimately carried into every corner of the empire—remain among the most collectible and admired achievements of Qing Dynasty craftsmanship.

.jpg)

Puyi, last Emperor of the Qing Dynasty

(Image: Wikipedia)

A Miniature Art Form Embraced by the World

The Chinese snuff bottle has long since left its utilitarian origins behind, taking its place among the most celebrated miniature art forms in the world. Collectors from across the globe seek out the finest examples—Qing Dynasty imperial pieces, intricately carved jade and crystal bottles, enamel works of remarkable delicacy, and inside-painted bottles whose intricate interior scenes speak to a tradition of virtuosity that has never faded. Since 1968, The International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society has served as the essential shepherd of this legacy, connecting collectors, advancing scholarship, and ensuring that the history and artistry of the form continues to be understood and appreciated by new generations.

What began as a practical solution to a humidity problem—a tiny stoppered bottle standing in for an ill-suited European box—evolved through centuries of imperial patronage, regional craftsmanship, and global trade into something few could have anticipated: an art form as intimate as it is ambitious, small enough to hold in the palm of a hand and vast enough to command a lifetime of devotion.

Attendees of the 2025 ICSBS Convention

_with_her_Two_Eldest_Sons_-_Google_Art_Project-min.jpg)

.jpg)